Summary:

Shark populations have steeply declined worldwide due to unsustainable overexploitation and in this the Caribbean region is no exception. Since the 1990s many initiatives have been developed to protect the most threatened species. Sharks play an important ecological role in tropical marine ecosystems and represent an important economic potential in the context of ecotourism. As the Netherlands has traditionally shown strong international leadership and commitment in biodiversity protection, a key ambition of the new Dutch Caribbean Nature Policy Plan 2013-2017, developed jointly with the Dutch Caribbean islands, is the effective implementation of shark protection.

This report provides the necessary review and background on which to base such an endeavour. In 2012 27 species of sharks and rays were documented to be present in a deskstudy by IMARES, and six other species were listed to be tentatively present according to the IUCN Shark Specialist Group. In 2013 three new species were documented in field surveys carried out by IMARES. For these species this report provides an overview of available scientific knowledge on life history characteristics, distribution, abundance and population status in the Caribbean. The life history characteristics of slow growth, late maturity and low fecundity make sharks very vulnerable to overfishing and reduce their ability to recover from past overfishing. Because of their life history characteristics and their coastal habitat use for specific life stages, destruction of their main habitats and nursery grounds also has a relatively large impact on shark populations.

The main threats to address in a shark protection plan are fishing mortality and habitat quality. Although directed shark fisheries are not occurring in the Dutch Caribbean, there are additional concerns to global shark populations, which are mixed-species fisheries, bycatch and Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. Sharks do occur as bycatch in artisanal fisheries in the Dutch Caribbean and illegal fishing by foreign vessels also occurs occasionally.

Public environmental awareness and support for management measures are a key determinant for the successful implementation of a shark protection plan. As part of this research a questionnaire was distributed amongst three key coastal resource user groups: fishermen, sport divers and local residents. It appeared there was no consensus on the perception of the change in biodiversity and abundance of sharks and rays. However, a decisive majority of the respondents was in favour of shark protection and half of the fishers was in favour to manage bycatch. Respondents were asked to rank specific measures in order of importance. The most appreciated measure for fishermen was enforcement including meaningful penalties and the most appreciated measures for the other respondents were a ban on shark finning and landing of sharks, followed by enforcement and immediate release of bycatch. However, in the opinion of some fishermen sharks are considered a pest, which are not specifically targeted, but when caught are consumed or sold like any other fish. Awareness raising of especially fishermen and children was added by several divers and residents as an important additional protection measure.

Throughout the world, sharks are playing an increasingly important role in island economies as an important natural attraction for eco-based recreation and tourism. A recent study has shown that a single shark can represent an average touristic resource value of US$ 2.64 million. Consequently, shark protection is taking flight around the world, including the Caribbean. In the last 3 years the region has seen the implementation of shark National Plan Of Action (NPOA) in the Bahamas, Honduras and Venezuela. Because the most destructive industrial-scale fishery practices (directed shark fisheries, shark finning, long-lining and gillnetting) have never been important in the Dutch Caribbean, the development and effective implementation of a shark NPOA is much simpler than in most situations. The overall feasibility for successful shark conservation are high due to a number of other factors listed in this report.

Worldwide the use of sanctuaries is the main conservation tool. We therefore propose the establishment of a shark sanctuary as the main cornerstone to a Dutch Caribbean shark NPOA. This report outlines the ecological arguments for the establishment of a shark NPOA and sanctuary(ies), as well as the typical issues that need to be addressed. Legal designation of a shark sanctuary would form the first and most important step which provides the framework for all broader (international cooperation) and in depth (knowledge and conservation development) initiatives. Once a sanctuary is established, the fuller implementation of a shark NPOA should be seen as a gradual process, involving development of knowledge, policy, rules and regulations, public and stakeholder participation. In this, the Netherlands would follow and importantly reinforce the efforts of other nations who have already established NPOAs based on shark sanctuaries within the region.

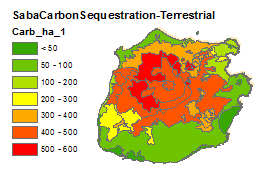

The most promising area for establishment of a shark sanctuary is the little-fished Saba Bank as this area of unique biodiversity has the best shark population status, has recently already acquired national protected status and an active management structure, as well as international status as an EBSA and PSSA including IMO anchoring prohibition. Furthermore, a shark sanctuary for this area could importantly reinforce government plans to locate the first (part) of a Dutch Caribbean Marine Mammals Sanctuary at the Saba Bank. The shark population present presents unique research opportunities that could also generate considerable economic spin-off for the islands in terms of scientific research and knowledge development.

Management Recommendations:

- Develop a simple and holistic shark NPOA based importantly on the use of one (or more) shark sanctuaries

- Set up a shark research program combining on the one hand low tech opportunistic approaches (allowing participation of stakeholder groups for awareness and community support) and on the other hand using high tech approaches (genetic, telemetry, video-monitoring) to allow thorough insights even though abundance may be low

- Start actively participating in regional shark conservation and ecosystem initiatives and seek active collaboration with sister sanctuaries of the region (Venezuela, Honduras, Bahamas)